Mr. Sumit is Business Head – Fluoro – Chemicals Specialty with Chemours India handling Fluoro-Chemicals Specialty Business for South Asia. Fluoro – Chemicals Specialty includes Fire Suppression Clean Agents, Foam Expansion Agents, Electronic Gases, and Specialty Cleaning Solvents.

Sumit is a Graduate Mechanical Engineer and Masters in International Business from Indian Institute of Foreign Trade Delhi.

He is a well – known, experienced and thoroughly trained Professional having Diversified Experience of17 years in Refrigeration, Air-conditioning and Fire-Industry. Sumit has worked with Domain expert Companies like DuPont, Blue Star, Electrolux, Hoover, Frigoglass.

While working with Experts throughout his career he has gained skill, expertise and developed competencies in Business Leadership, Sales and Marketing Management, Business Development, Product Management, Marketing Communication, Key Account Management and Customer Service Management.

HFC Regulations are the most misinterpreted and misunderstood topic in the clean agent market, despite these Regulations being based on sound scientific principles. Let's take a look at the basic facts and their implications, as demonstrated in recent actions by the Government of India, the European Environmental Agency and the US EPA.

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT: THE SCIENTIFIC FACTS

Ozone Depletion. Since hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) do not contain chlorine or bromine, they do not contribute to the destruction of stratospheric ozone; as a result, HFCs are not subject to the provisions of the Montreal Protocol, which pertain only to ozone depleting substances (ODSs).

Ozone Depletion. Since hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) do not contain chlorine or bromine, they do not contribute to the destruction of stratospheric ozone; as a result, HFCs are not subject to the provisions of the Montreal Protocol, which pertain only to ozone depleting substances (ODSs).

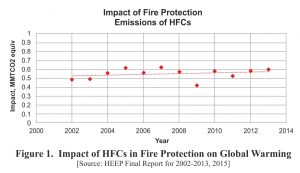

Global Warming. The impact of HFCs in fire protection on global warming/climate change is often misunderstood and misrepresented. It is important to understand that the impact of a gas on climate change is a function of both the GWP of the gas and the amount of the gas emitted. For example, carbon dioxide (CO2) has one of the lowest GWP values of all GHGs (GWP=1), yet emissions of CO2 account for approximately 85% of the impact of all GHG emissions – due to the massive amounts of CO2 released into the atmosphere from numerous sources. Clearly the GWP value by itself cannot be employed to evaluate the environmental sustainability of a particular compound. Emissions of HFCs from fire suppression applications are extremely low, hence the impact of these emissions on climate change is negligible.

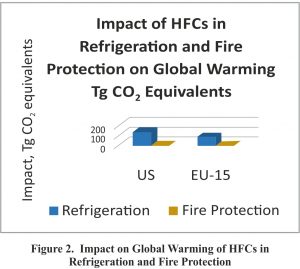

Factual information related to the environmental impact of HFCs in fire protection is available from several independent sources including the US EPA [1] and the European Environment Agency [2], and indicate that the contribution to global warming of HFCs in fire protection is negligible. For example, in the US the impact on global warming of HFCs in fire protection represents 0.019% of the impact of all greenhouse gases on global warming. For the EU-15 countries, the impact on global warming of HFCs in fire protection represents 0.05% of the impact of all greenhouse gases on global warming.

An examination of historical data reveals that the contribution of HFCs in fire protection to global warming has remained essentially constant for almost a decade.As seen in Figure 1, the 2015 report from the HFC Emissions Estimating Program (HEEP) indicates that the impact of HFCs in fire protection is not increasing but has remained essentially steady for more than a decade, despite the growing installed base.

NOT ALL HFCsARE CREATED (OR TREATED) EQUALLY

As seen in Figure 2, the impact on global warming of HFCs in fire protection applications is dwarfed by the impact of HFC emissions from other much larger and much more emissiveHFC applications such as refrigeration.

As seen in Figure 2, the impact on global warming of HFCs in fire protection applications is dwarfed by the impact of HFC emissions from other much larger and much more emissiveHFC applications such as refrigeration.

Regulatory bodies understand the above scientific facts, and to date HFCs in fire suppression applications have been subject to different sets of regulations. For example, the original European Union F-Gas Regulation has since 2006 treated HFCs in highly emissive applications such as mobile air conditioning (MAC) differently than HFCs in fire protection applications – HFCs in MAC applications are regulated under a separate MAC Directive of the F-Gas Regulations.

US EPA FINAL RULE 20

On July 2, 2015 the U.S. EPA released a prepublication version of its Final Rule on the Change of Listing Status for Certain Substitutes under the Significant New Alternatives Policy (SNAP), also known as US EPA Final Rule 20. The reason for the listing status changes is explained by the US EPA on the first page of the document: “We make these changes based on information showing that other substitutes are available for the same uses that pose lower risk overall to human health and the environment.” The Final Rule will change the approval status of certain HFCs in refrigeration, foam expansion and aerosol propellant applications.

The effects of Proposed Rule 20 on HFCs in fire protection? None whatsoever. Under Rule 20 there will be no changes to the listing status of any HFC in any fire protection application, and the HFC-based clean agents continue as approved, effective and sustainable fire protection solutions. The Final Rule is consistent with the negligible impact of HFCs in fire protection on global warming, and with the fact that no alternatives to the HFC clean agents are currently available which match the overall combination of proven performance, safety in use and cost effectiveness offered by the HFC clean agents.

EUROPEAN UNION F-GAS II REGULATIONS

Original EU F-Gas Regulation. Regulation (EC) No 842/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council on certain fluorinated greenhouse gases, the original “F-Gas Regulation,” was published on May 17, 2006, and entered into force in 2007. The primary objective of EC 842/2006 was to prevent and reduce emissions of HFCs. EC 842/2006 included in its Articles 3 through 10 requirements related to the prevention of leakage (containment), recovery, personnel training, record keeping, reporting and labeling, all with the goal of the reduction of unnecessary emissions. The regulation recognized that fire suppression applications are essentially non-emissive, and imposed no restrictions on the use of HFCs in fire suppression applications. For a detailed review of the original F-Gas Regulations and HFC clean agents, see the February 2013 issue of International Fire Protection.

EU F-Gas II Regulation. Regulation (EU) No 517/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 April 2014 on fluorinated greenhouse gases and repealing Regulation (EC) No. 842/2006, the “F-Gas II Regulation,” was published on May 20, 2014, and entered into force on 1 January 2015. Consistent with US EPA Rule 20, the EU F-Gas II Regulation also recognizes the value and sustainability of the HFC clean agent fire protection technologies. Since HFCs in fire protection have a negligible impact on global warming, restricting HFC use in fire protection applications would not provide any significant reduction in global warming.

The EU F-Gas II Regulation retains Articles 3 to 10 from the original EU F-Gas Regulation related to containment, recovery and training; as a result, these Articles are already being complied with by the fire protection industry. Requirements related to containment including leakage prevention, repair and inspection schedule are satisfied by the existing inspection regimes established by the ISO 14520, EN 15004 or NFPA 2001 standards. Recovery related requirements are currently being met by the numerous commercial entities already actively involved in the recovery and reclamation of HFC-based clean fire extinguishing agents. Training and certification programs for personnel involved in the handling of fluorinated GHGs have been in place for more than a decade within the fire protection sector. In summary, the requirements of Articles 3 through 10 of the F-Gas II Regulation involve activities already part of any responsible product stewardship program and impose no restrictions on the use of HFC clean agents.

EU F-GAS II ALLOCATION QUOTAS

A significant change from the original EU F-Gas Regulation of 2006 is the establishment of allocation quotas. Article 16 of the F-Gas II Regulation establishes an allocation of quotas for placing HFCs on the market in the EU each year; Article 15 requires that producers and importers not exceed their quota. Under Article 16 a reference value, based on the annual average of quantities of HFCs (expressed in terms of CO2 equivalents) the producer or importer reported to have placed on the market from 2009 to 2012, is calculated in accordance with Annex V of the Regulation; quotas are then allocated employing the reference value and the allocation mechanism described in Annex VI of the Regulation.

A significant change from the original EU F-Gas Regulation of 2006 is the establishment of allocation quotas. Article 16 of the F-Gas II Regulation establishes an allocation of quotas for placing HFCs on the market in the EU each year; Article 15 requires that producers and importers not exceed their quota. Under Article 16 a reference value, based on the annual average of quantities of HFCs (expressed in terms of CO2 equivalents) the producer or importer reported to have placed on the market from 2009 to 2012, is calculated in accordance with Annex V of the Regulation; quotas are then allocated employing the reference value and the allocation mechanism described in Annex VI of the Regulation.

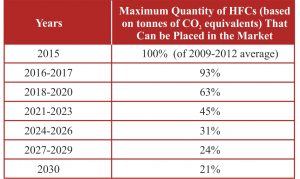

The allocation framework of the F-Gas II Regulation does not inhibit or limit the sale of HFCs into the fire suppression market.The allocation scheme represents an overall “cap and reduction” of HFCs on a GWP-weighted basis over a specific time period – a “phase-down,” NOT a “phase- out” of HFCs. The phase-down mechanism involves a gradually declining cap on the total placement of bulk HFCs (in tonnes of CO2 equivalents) on the market in the EU with a freeze in 2015, followed by a first reduction in 2016 and reaching 21% of the levels sold in 2009 to 2012 by 2030.

An important aspect of this allocation scheme is that it does not restrict the amount of any particular HFC that can be placed on the market or any the amount of HFCs used in any particular application; it simply restricts the total CO2 equivalents of all HFCs that can be placed on the market. Table 2 shows the schedule as indicated in Annex V of the Regulation.

OZONE CELL, MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT & FOREST (MOEF), GOVERNMENT OF INDIA

The Ozone Cell, MOEF, Government of India proposal forms the basis of India's plan for the regulation of HFCs. A key component of the Ozone Cell plan is a gradual phase-down (NOT phase-out) of HFCs in certain applications with a baseline starting in 2030 and phasedown completion in 2050. Under the plan, alternatives to HFCs should be of lower cost and provide improved efficiencies. In addition, transition costs should be affordable to developing economies.

The plan is consistent with the recent regulations passed in the EU and US, recognizing both the negligible impact of HFCs in fire protection on global warming and the lack of alternatives to the HFC clean agents which match the overall combination of proven performance, safety in use and cost effectiveness offered by the HFC clean agents. With specific regard to fire protection, the Ozone Cell plan places no restrictions or limitations on the use of HFC clean agents in fire protection.

CONCLUSION

The emissions of HFCs in fire protection are extremely low, hence their impact on global warming is negligible. As a result, restricting HFC use in fire protection applications would not provide any significant reduction in global warming and efforts beneficial to the environment are more productively focused on other sectors with much larger impacts. Regulators clearly understand this, as evidenced by the recent regulatory decisions of the US EPA and the EU F-Gas II Regulation.The recent regulatory decisions of the US EPA and the EEA are based on sound science and recognize the value, importance, and non-emissivity of HFC clean agents in fire protection.

With the recent major regulatory decisions in the USA and Europe, HFCs in fire protection remain approved, effective and sustainable fire protection solutions.

REFERENCES

1. US EPA Report 430-R-15-004 (2015)

2. EEA Technical Report No. 09 (2014).

3. EEA Technical Report No. 15 (2013).

4. Website: Ozone Cell, Ministry of Environment & Forest, Government of India.

For further details Please Contact: Sumit Grover : +91 98104 40816

Email: sumit.grover@chemours.com