A simple way of minimising firefighters' exposure to hazardous chemicals on the job, after the job, and between jobs.

It all started in 2006, when the fire station in a small town in northern Sweden began to implement simple strategies to minimise the health effects of firefighting on its personnel. Using modest means, the exercise turned out to be such a success that it has earnt awards, EU recognition, and implementation in other countries.

The program began under the name 'Healthy Firefighters', but has become known as 'The Skellefteå Model' after the country town where it was first developed.

In 2011, the Skellefteå Model was awarded the prestigious Good Practice Award from the European Agency for Safety and Health and won international acclaim. Both the European Trade Union Institute and the European Federation of Public Service Unions adopted the program.

Main emphasis

Firefighters run a greater risk of contracting serious illnesses than the rest of the population. In 2007, the World Health Organisation (WHO) established a connection between firefighting and a range of cancers, including testicular, prostate, and lymphatic. Firefighters may also suffer other health problems that are not associated with cancer, such as diseases of the heart, immune system, muscles, nerves, organs, hormone regulation, and possibly reproduction.

A fire incident almost always entails the release of hazardous substances, many of them unknown. There is no way of knowing what harmful chemicals may be present. Therefore, firefighters rely on various protective devices. The focus of the Skellefteå Model is safer procedures for handling contaminated clothing and equipment – especially after the job is finished. This includes simple routines at the site, during transportation, and upon return to the fire station.

In short, the program gives simple and practical advice on how to minimise the hazardous materials firefighters are exposed to, resulting in a safer work environment and improved well-being.

Risk moments

The firefighter's job may seem risky enough by dint of the fire itself, but there are additional risk factors:

- Hidden hazards can often go undetected by the firefighter, e.g. by smell or taste. Even the tear ducts and the natural coughing reflex can be numbed or dampened.

- Changing work shifts may lead to physical and mental stress.

- Extreme physical strain and thermal stress are risk factors that take their toll on the well-being of the fire professional.

- Not a profession, an identity: both fire personnel and the public often see the firefighter as an identity, not an employee. This may explain why many firefighters see their work as a 'job for life'. Long-term employment means long-term exposure to hazards.

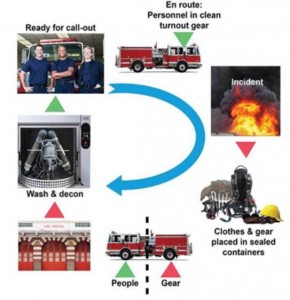

The three-tiered structure of the Skellefteå Model.

Into the unknown

As the Skellefteå Model focuses on unknown hazardous substances, the subject of combustion gases plays a major role in the program. Heat and flame may generate more than 400 different harmful substances, including benzene, dioxin, formaldehyde, polyaromatic hydrocarbons, and vinyl chloride – and that's only from 7 common plastics. In a house fire, many more combustion gases are generated.

The firefighter may be exposed to these hazardous substances in three ways: inhalation, skin absorption, and swallowing.

Inhalation is simple to understand: if respiratory protection is not worn – even for a very short time – the firefighter will inevitably breathe in airborne materials.

Skin absorption can be deceptive. Not only is any opening in the turnout gear a possible entry point for contaminants, but just touching your skin with a dirty glove is a certain way of letting foreign materials reach the skin. This is particularly important when it comes to removing soiled clothing and equipment after the job. Add to this that chemicals commonly are absorbed more readily by warm and sweaty skin.

Swallowing hazardous materials can happen when not wearing any respiratory protection, or momentarily removing the respirator. Most ingestion happens after a job is finished, when the firefighter perhaps has some food to eat, enjoys a sweet or a bubble gum, takes a drink, or smokes. Bottles, dishes, packaging, and one's own fingers may be contaminated. Furthermore, just swallowing saliva may 'activate' harmless substances into hazardous ones.

These three means of entry into the body are insidious. The absence of detectable characteristics in many hazards may lead to failure to wear personal protection when it is needed.

Some firefighters may resort to simple but largely ineffectual practices, such as breathing through the nose in the belief that the nose hairs will filter out airborne hazards (false), hold one's breath or try to breathe less (counterproductive), or breathing into the elbow or collar (useless).

It's in the mix

One problem in firefighting situations is that not only may there be unknown contaminants present, but often more than one. One chemical blending with another can cause far greater damage than each substance on its own. As mentioned, a contaminant may be harmless unmixed, but might become harmful when mixed with saliva. The combined effects of more than one chemical can be graded as follows:

- No effect.

- Added effect (each substance adds its own harmful effect).

- Counteractive effect (the substances cancel each other out).

- Synergistic effect (the combined effect is greater than that of each chemical).

- So, what is the Skellefteå Model?

The Skellefteå Model addresses routines, practices and work flows that can be easily and inexpensively implemented. The program is an action chain based on a three-tiered 'pyramid':

Knowledge and insight pave the way to acceptance of change. By having a good grasp of possible hazards and how exposure to them can be minimised, firefighting personnel will have a much better grounding – indeed, reason – for cooperation, participation, and implementation of simple but necessary changes that need to be done to the fire station, vehicles, and work routines. Better knowledge is also essential for eliminating old methods, in-grained routines, and flawed practices.

Routines and flows can simply be described as (a) fire personnel being transported to the fire site wearing clean clothes, carrying clean equipment, in a clean vehicle; (b) performing the firefighting using personal protection; and (c) personnel changing into clean clothes before returning to the fire station, wearing clean clothing in the truck, and being well separated from all contaminated clothing and equipment. At the fire station, all contaminated items are to be immediately cleaned, washed and prepared for the next callout.

Tools may include the simplest of facilities, such as vats for soaking hoses and air-tight containers for contaminated clothing and equipment, to more complex items such as decontamination washing machines specially designed for turnout gear and BA sets.

Some post-callout guidelines

The Skellefteå Model recommends that some very simple guidelines be followed, every time, every callout. Most of the guidelines have to do with after-the-job routines:

- Turnout gear and equipment must not be worn on the way back to the station – especially not inside the cabin of the vehicle.

- Do not touch helmets, gloves, clothing or boots with bare hands.

- Be aware that helmets are close to the face and mouth – easy to spread contaminant.

- Boots usually have soles with deep grooves. These can harbour hazardous materials.

- BA sets are often removed too soon. They should always be exchanged for filter respirators. A filter respirator should always be part of the turnout gear, and stored in or on the clothing.

- Soiled equipment, such as BA sets, tools, cameras etc. should be stored in airtight containers on the way back to the station, AWAY from personnel and the cabin of the truck. The same goes for contaminated clothing.

- Hoses are best kept soaked in water.

- Personnel should enter the vehicle only wearing clean clothes.

- At the fire station, all equipment and clothing should be cleaned and washed straight away.

- When handling contaminated equipment and clothing, skin and respiratory protection must be worn.

It is common that decontamination routines are started by one person and finished by another. Personnel must brief each other as to the nature of the contamination, and not treat all items as one and the same.

Fire-station practices

There is a risk that fire-station practices become sheer routine, and end up as 'habitual blindness': things are treated with indifference, even if they constitute obvious hazards – this phenomenon is often explained as a parallel with anti-smoking cigarette packaging, where the smoker 'looks but does not see'. Most fire-station routine faults stem from only a few factors:

- Carelessness (fatigue; 'job's done' attitude).

- Culture ('we've always done it this way').

- Logistics (layout of premises; circuitous work flow).

- Lack of knowledge (real or deliberate ignorance of hazards).

- Behaviour (perhaps peer-driven).

Some of these 'lapses' can manifest themselves in thoughtless safety slips, such as turnout gear being stashed away upon return, without being decontaminated or washed. Another common blunder is the belief that the BA set will be used so soon again that it is pointless to clean it.

Basic fire-station checklist

- Routines are in place for decontaminating turnout gear, BA sets, tools and other equipment immediately upon return.

- Turnout gear and equipment are transported separately from personnel on the way back to the station.

- Turnout gear and equipment are washed and dried after every use.

- Outer clothes are handled and cleaned separately from other clothing.

- BA sets are decontaminated prior to checking, testing or repairing.

- The same procedures are performed after both

- major and minor emergencies, as well as training exercises.